Managing Software Debt

Continued Delivery of High Values as Systems Age

Many software developers have to deal with legacy code at some point during their careers. Seemingly simple changes are turned into frustrating endeavors. Code that is hard to read and unnecessarily complex. Test scripts and requirements are lacking, and at the same time are out of sync with the existing system. The build is cryptic, minimally sufficient, and difficult to successfully configure and execute. It is almost impossible to find the proper place to make a requested change without breaking unexpected portions of the application. The people who originally worked on the application are long gone.

How did the software get like this? It is almost certain the people who developed this application did not intend to create such a mess. The following article will explore the multitude of factors involved in the development of software with debt.

What Contributes to Software Debt?

Software debt accumulates when focus remains on immediate completion while neglecting changeability of the system over time. The accumulation of debt does not impact software delivery immediately, and may even create a sense of increased feature delivery. Business’ responds well to the pace of delivered functionality and the illusion of earlier returns on investment. Team members may complain about the quality of delivered functionality while debt is accumulating, but do not force the issue due to enthusiastic acceptance and false expectations they have set with the business. Debt usually shows itself when the team works on stabilizing the software functionality later in the release cycle. Integration, testing, and bug fixing is unpredictable and does not get resolved adequately before the release.

The following sources constitute what I call software debt:

- Technical Debt[1]: those things that you choose not to do now and will impede future development if left undone

- Quality Debt: diminishing ability to verify functional and technical quality of entire system

- Configuration Management Debt: integration and release management become more risky, complex, and error-prone

- Design Debt: cost of adding average sized features is increasing to more than writing from scratch

- Platform Experience Debt: availability and cost of people to work on system features are becoming limited

Software Debt Creeps In

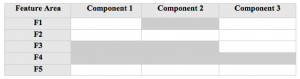

Figure 1.1: A relatively new system with little debt accrued.

Figure 1.1 displays a system that has minimal amount of software debt accrued. A few low priority defects have been logged against the system and the build process may involve some manual configuration. The debt is not enough to significantly prolong implementation of upcoming features.

Business owners expect a sustained pace of feature development and the team attempts to combine both features and bugs into daily activities, which accelerates the accrual of debt. Software debt is accruing faster than it is being removed. This may become apparent with an increase in the number of issues logged against the system.

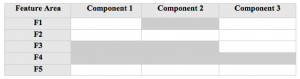

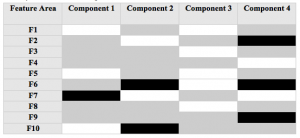

Figure 1.2: An aging software system slowly incurs significant debt in multiple functional areas.

As a system ages, small increments of software debt are allowed to stay so the team can sustain their velocity of feature delivery. The team may be complaining about insufficient time to fix defects. Figure 1.2 shows a system that has incurred software debt across all functional areas and components.

At this point, delivery slows down noticeably. The team asks for more resources to maintain their delivery momentum, which will increase the costs of delivery without increasing the value delivered. Return on investment (ROI) is affected negatively, and management attempts to minimize this by not adding as many resources as the team asks for, if any.

Even if business owners covered the costs of extra resources, it would only reduce the rate of debt accrual and not the overall software debt in the system. Feature development by the team produced artifacts, code, and tests that complicate software debt removal. The cost of fixing the software debt increases exponentially as the system ages and the code-base grows.

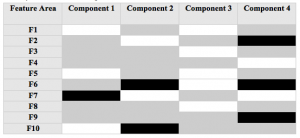

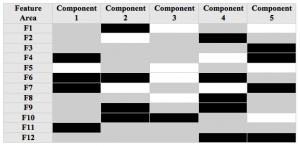

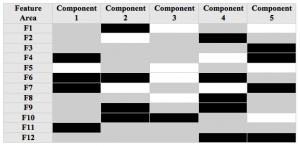

Figure 1.3: The aging system has accrued significant debt in all functional areas and components.

Software debt in the system continues to accrue over time, as shown in figure 1.3. At this point, new feature implementation is affected significantly. Business owners may start to reduce feature development and put the system into “maintenance” mode. These systems usually stay in use until business users complain that the system no longer meets their needs.

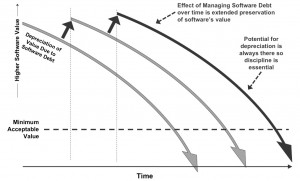

Managing Software Debt

There are no magic potions for managing software debt. Software can accrue debt through unforeseen circumstances and shortsighted planning. There are some basic principles that help minimize software debt over the lifespan of the product:

- Maintain one list of work

- Emphasize quality

- Evolve tools and infrastructure continually

- Always improve system design

- Share knowledge across the organization

- And most importantly, hire the right people to work on your software!

Maintain One List of Work

One certain way to increase software debt is to have multiple lists of work. Clear direction is difficult to maintain with separate lists of defects, desired features, and technical infrastructure enhancements. Which list should a team member choose from? If the bug tracker includes high priority bugs, it seems like an obvious choice. However, influential stakeholders want new features so they can show progress to their management and customers. Also, if organizations don’t enhance their technical infrastructure, future software delivery will be affected.

Deployed software considered valuable to its users is a business asset, and modifications to a business asset should be driven from business needs. Bugs, features, and infrastructure desires for software should be prioritized together on one list. Focus on one prioritized list of work will minimize confusion on direction of product and context-switching of team members.

Emphasize Quality

An emphasis on quality is not only the prevention, detection, and fixing of defects. It also includes the ability of software to incorporate change as it ages at all levels. An example is the ability of a Web application to scale. Added traffic to the web site makes performance sluggish, and becomes a high priority feature request. Failed attempts to scale the application result in a realization that the system’s design is insufficient to meet the new request. Inability of the application to adapt to new needs may hinder future plans.

Evolve Tools and Infrastructure Continually

Ignoring the potential for incremental improvements in existing software assets leads to the assets becoming liabilities. Maintenance efforts in most organizations lack budget and necessary attention. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standardizes on four basic categories of software maintenance in ISO/IEC 14764[2]:

- Corrective maintenance - Reactive modification of a software product performed after delivery to correct discovered problems

- Adaptive maintenance - Modification of a software product performed after delivery to keep a software product usable in a changed or changing environment

- Perfective maintenance - Modification of a software product after delivery to improve performance or maintainability

- Preventive maintenance - Modification of a software product after delivery to detect and correct latent faults in the software product before they become effective faults

Most maintenance efforts seek to prolong the life of the system rather than increase its maintainability. Maintenance efforts tend to be reactive to end user requests while business evolves and the technology decays.

To prevent this, attention must be given to all four categories of software maintenance. Budgets for software projects frequently ignore costs for adaptive, perfective, and preventive maintenance. Understanding that corrective maintenance is only part of the full maintenance picture can help an organization manage their software assets over it’s lifespan.

Improve System Design Always

Manage visibility of system design issues with the entire team. Create a common etiquette regarding modification of system design attributes. Support the survival of good system design through supportive mentoring, proactive system evolution thinking, and listening to team member ideas. In the end, a whole team being thoughtful of system design issues throughout development will be more effective than an individual driving it top down.

Share Knowledge Across the Organization

On some software systems there is a single person in the organization who owned development for 5 years or more. Some of these developers may find opportunities to join other companies or are getting close to retirement. The amount of risk these organizations bear due to lack of sharing knowledge on these systems is substantial.

Although that situation may be an extreme case of knowledge silos, a more prevalent occurrence in IT organizations is specialization. Many specialized roles have emerged in the software industry for skills such as usability, data management, and configuration management. The people in these roles are referred to as “shared resources” because they use their specialized skills with multiple teams.

Agile software development teams inherit team members with specialized roles, which initially is a hindrance to the team’s self-organization around the work priorities. Teams who adhere to agile software development values and principles begin to share specialized knowledge across the team, which allows teams to be more flexible in developing software based on priorities set by business. Sharing knowledge also reduces the risk of critical work stoppage from unavailable team members who are temporarily on leave.

Hire the Right People!

It is important to have the team involved in the hiring process for potential team members. Teams will provide the most relevant skills they are looking for, thus, allowing them to review and edit the job description is essential. Traditional interview sessions that smother candidates with difficult questions are insufficient in determining if the candidate will be a great fit. Augmenting the interview questions with a process for working with the candidate during a 1 to 2 hour session involving multiple team members in a real-world situation adds significant value to the interview process. Before hiring a candidate, teams members should be unanimous in the decision. This will increase the rate of success for incorporation of a new team member since the team is accepting of their addition.

Another significant hiring focus for organizations and teams is placing more emphasis on soft skills than technical expertise. I am not advocating ignoring technical experience. However, it is critical in an agile software development organization or team to have people who can collaborate and communicate effectively. Soft skills are more difficult to learn than most technical skills. Look for people who have alignment with the hiring team’s values and culture.

In Summary

As systems age they can become more difficult to work with. Software assets become liabilities when software debt creeps into systems through technical debt, quality debt, configuration management debt, design debt, and platform experience debt.

Applying the six principles in this article will lead to small changes that over time will add up to significant positive change for teams and organizations. The goal of managing software debt is to optimize the value of software assets for our business and increase the satisfaction of our customers in the resulting software they use.

References

- Ward Cunningham - “Technical Debt” - http://c2.com/cgi/wiki?TechnicalDebt

- “ISO/IEC 14764: Software Engineering — Software Life Cycle Processes — Maintenance” - International Organization for Standardization (ISO), revised 2006

5 Comments »